The situation following the first Battle of Zenta (1686–1697)

The liberation campaign during the autumn of 1686 successfully drew the Turks out from a significant part of Hungary. Later Buda was liberated, followed by Szeged, Szabadka and Zenta. The Turkish fortress in Zenta was closed down in November 1686 together with the 11 forts and palisades of the Szeged Sanjak, after the Turks had been defeated near Orompart in the first Battle of Zenta in October 1686. Following the withdrawal of the Turks, the first record from 1688 testifies that a Serbian military battalion serving the Austrian military command operated in Zenta. Meanwhile, the Turks managed to force the Christian troops that had already reached Macedonia, to retreat beyond the lines of the Sava and the Danube, after which the Viennese military leadership could stop the Turks, who were planning to recapture Hungary, in 1691 at Slankamen, only at the expense of great sacrifices. Until the middle of the 1690s, there was no major campaign in this area, only mutual raids and minor acts of war in which the Serbs of Zenta were also involved.

Preparations preceding the battle – the opponents

Mustafa II, who came to the throne in 1695, issued a Sultan proclamation in which he foresaw renewal and new conquests. The Viennese leaders, after they had received intelligence about the preparations of the Turks, created their war plan in late May. For the time being, the purpose of the operation was to cover Petrovaradin and to closely monitor the enemy. Eugene of Savoy was appointed commander in chief on July 5, 1697, following which he travelled to Küllőd (Kolut) in order to take up his post and to keep watch over the 25 infantry and 9 cavalry units there.

The opponents:

Mustafa Mehmed Oglu II (1664–1703) was a Turkish sultan who ruled between 6 February 1695 and 22 August 1703. He propagated renewal, introduced financial reforms, rebuilt his fleet, and attempted to reclaim the lost areas.

Eugene de Savoy, François Eugène de Savoie-Carignan, Prince of Savoy (1663-1736) was one of the greatest generals of the New Age. His extraordinary military talent was revealed during the liberation of Vienna in 1683, as well as during a following series of successes in Hungary: at Esztergom in 1685, Buda in 1686, Nagyharsány in 1687, and Belgrade in 1688. In 1693 he was promoted to a field-marshal. In 1697 Emperor Leopold I appointed him the commander-in-chief of the Imperial forces.

Marching of the armies

On August 20, 1697, the Turkish army crossed the Danube at Pančevo, and the Sultan divided his army into two parts. A division numbering 20,000 men led by Djafer Pasha started to move towards north to ford the river Maros and so invade the territory of Hungary, while the main part of their army was heading towards Titel along the left bank of the Danube. As a reaction to this, Savoy’s troops started moving northward to meet with the armies of the Duke of Vaudémont and of Count Rabutin, who was coming from Transylvania, at Szeged.

The Duke of Savoy, who was proceeding north, reached the Csík river on August 26 and headed for Zenta, then met Rabutin’s vanguard at a distance of one hour from the village. In the meantime, the Sultan ordered his advancing troops that had already reached to return to Titel so that he could invade Petrovaradin. The Duke of Savoy, who was waiting near Zenta, was informed that the Turks had captured Titel while he was still waiting for Rabutin to arrive from Transylvania by the Csík river. The two forces were finally joined on 31 August and then returned to the south to secure Petrovaradin from the Turkish army that had already been merged near Kovilj. When news came to the sultan that the Duke of Savoy was once again positioned at Novi Sad with his concentrated army, the Turks changed their battle plan and named the seizure of Szeged and the military warehouse the next goal of their campaign.

Arrangements before the battle, the formation of troops

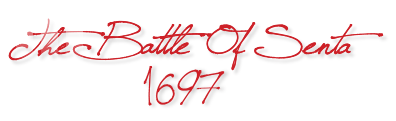

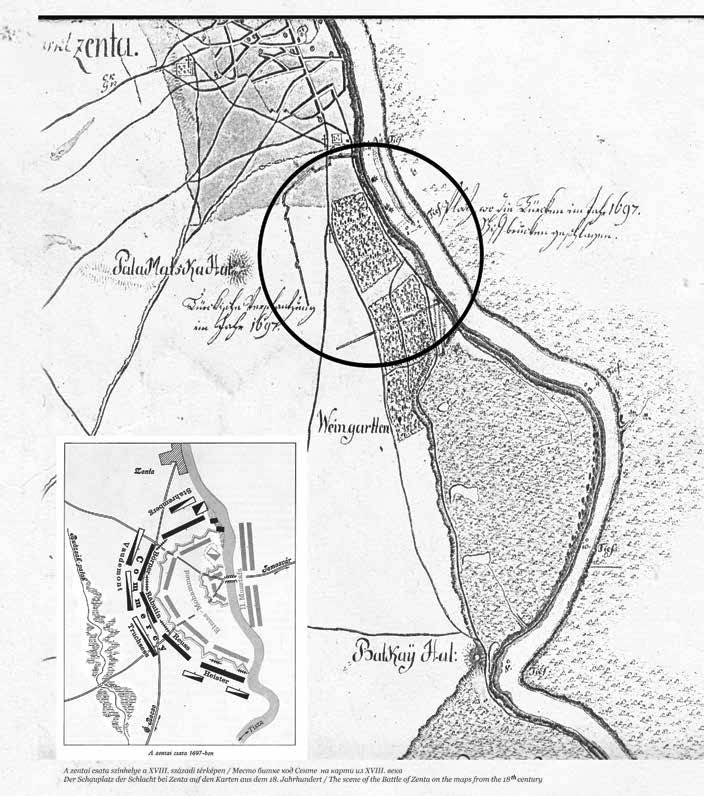

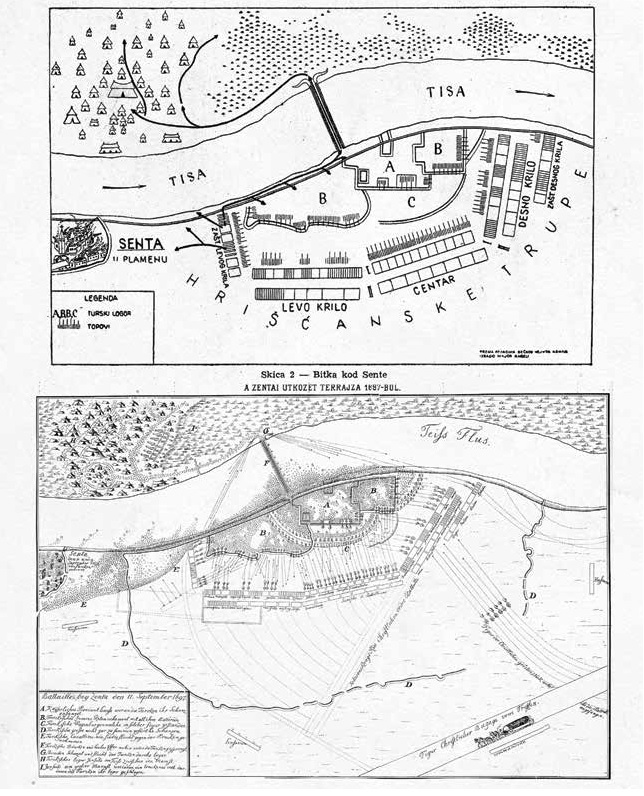

On September 7, the Turkish army headed north towards Szeged, but after they had learned that Szeged was also under strong military defence, they changed their plans again: they decided to ford the Tisza at Zenta. Immediately below Zenta, there was an elongated island in the middle of the Tisza, which offered a very favourable position to build a bridge – in fact this island will later become the scene of the Battle of Zenta. Most of the Turkish army did not position themselves directly by the river, but rather made positions farther and created a rampart of carriages, while the French army engineers of the Sultan began the construction of a 60-ship pontoon bridge at the so-called provianthouse (military warehouse). The bridge was made up of longboats linked with bulks and fastened with leather belts, which were then covered with cross planks. The Turks reinforced the barricades around the army warehouse at the bridgehead, while the building itself was surrounded by an approximately 500 feet long, deep ditch with a strong rampart of carriages. It formed the inner defensive line of the bridgehead. In addition, a semi-circle palisade with a radius of 1000 feet was constructed with bulwarks and openings for performing sudden breakouts, but its northwest side was left unfinished.

Savoy, with his entire army having arrived in the meantime, headed north again, following the Turkish troops and arriving to Becse on September 10th. On September 11th, before sunrise, Eugene broke camp and marched toward Zenta. With his cavalry and some artillery, he broke away from his camp in order to get properly informed about the crossing of the Turkish troops, and with further information gained on the course, he stopped for about an hour away from the Turkish army and left the rest of his army behind. After they had arrived in the afternoon, Eugene began to plan his battle formation. The battle was held in the afternoon from 3 am to 4 pm. The Duke of Savoy pushed the right wing toward the Tisza, while he stretched the the left wing across the plane as much as the number of troops allowed. Heister, Truchsess, Gronsfeld and Salaburg were in charge of the right wing and the left wing was entrusted to Starhemberg, Vaudémont, Corbelli and Hasslingen. He himself took a position in the middle with Commercy, Rabutin, Börner, and Reuss. The Austrian army numbered about 70,000 men; there were 51 battalions of infantry, 112 of cavalry and 60 cannons. Both Hungarians and Serbs fought in the battle: Count János Pálffy, Count (and General) István Dessewffy and Colonel Pál Deáky, as well as Jovan Tekelija and the Serbian Militia of Zenta.

The second Battle of Zenta (September 11, 1697)

The Turkish pontoon was being built day and night on September 10 and was finally completed by noon of the following day. The Sultan and a two thousand of his entourage were the first to cross the bridge, then followed by the artillery. After that, the janissaries and the rest of the army began to transfer their gear and luggage. The Duke of Savoy, who was desperately after the Sultan, reached the place of the battle at about three o’clock in the afternoon, while the Turks were trying to cross the bridge amidst a great commotion. He then grasped the great window of opportunity and decided to ride ahead and to attack the ramparts with 3000 cavalrymen and the same number of dragoons. The invading Christian army approached the enemy lines and while the Turkish cavalry left behind suddenly rushed towards the army of the Duke of Savoy, who personally led a part of his cavalry. The Turkish soldiers facing a strong and tough attack had to retreat into their trenches. General Starhemberg, who was ahead the left wing, then noticed that the pontoon was starting to lurch under the fleeing Turks, so he commanded his artillery to shoot at the bridge from the river bank. General Heister followed his lead from the right wing, so the pontoon broke in two under the cannon fire coming from the two sides and thousands of Turks met their death among the waves of the Tisza.

Meanwhile, the battalions of the left wing reached the bridgehead moving through the sandy banks of the Tisza and occupied the entrance of the bridge. The approximately 35,000 Turkish soldiers who had no reinforcement from the other side, were stuck between the trenches, so their position became hopeless. Eugen de Savoy, witnessing the twist of the battle, sent a reinforcement from the left wing reserve and from the centre to the bridgehead, which pushed among the ramparts, followed by the right wing led by their commander-in-chief. In the middle they also led heroic attacks against the ramparts, while the troops on the waterfront and in the water were in the grips of a bloody battle with the enemy. The soldiers did not have mercy for anybody, some of the pashas were executed by the enraged janissaries. Many of the Turks tried to flee the scene by throwing themselves into in the 300-meter-wide Tisza, however, most of them were finished off by fire of the musketeers and carabineers, others drowned in the thick of the fray. The intimidated Turkish army thought of fleeing rather than resisting, but only a few thousand were able to get to the opposite bank.

After the victory

The sultan watched the fall of his army from the other side, and fled with his remaining army to Timişoara. The next day, de Savoy crossed the Tisza with a part of the cavalry to assess the results of the battle and send a messenger to Vienna to inform Emperor Leopold I of the events and the bright victory. The armament and valuables left behind in the Turkish camp were of enormous value. The victorious army laid hands on the Sultan's seal stamp, 86 warlords, and so on. The balance of the victory was justified by Savoy's perfect timing of the attack: only 429 Imperial soldiers died (28 officers, 401 soldiers, there were 1598 wounded, including 133 officers and 1465 soldiers). The balance of the Turks, however, was tragic: the corpses of 25,000 soldiers covered the battlefield. In honour of the victory, the city of Vienna celebrated the Battle of Zenta on September 21, 1697 with a thanksgiving mass (te deum), a procession, a triumphant arc and by erecting columns (Vienna ad Zentam servata - Vienna saved by Zenta). The buildings and squares were decorated, and coins minted in memory of the battle were distributed among the people. Central Europe and Hungary were liberated with the battle of Zenta for a century and a half long Turkish rule.